The UK’s ‘Local Currencies’ Are Going Crypto

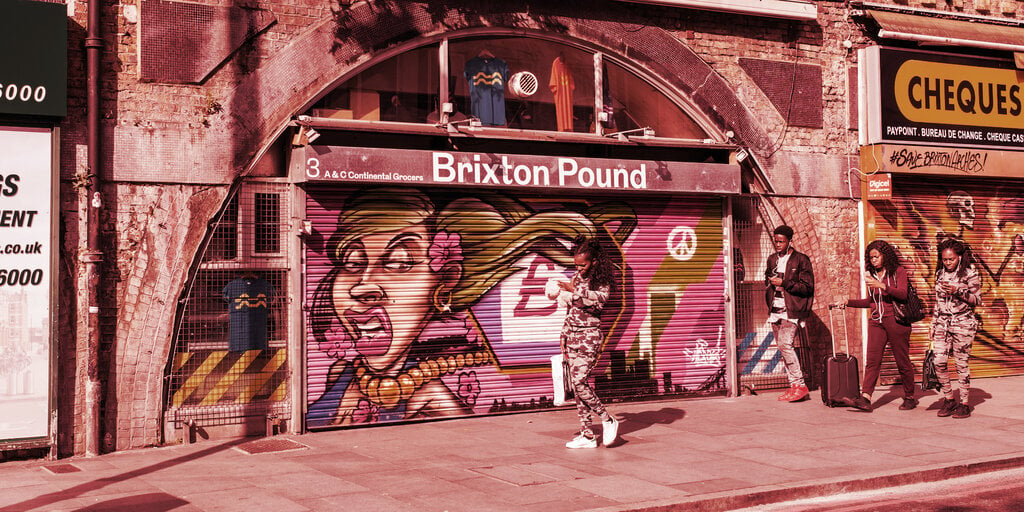

The Bristol Pound and the Brixton Pound were touted as the saviors of the British High Street—but their progress as local currencies was cut short, in part by fears over the use of physical cash during the coronavirus epidemic.

Now, inspired by cryptocurrencies, the two independent projects are drawing up plans to go digital in the form of tokens and, eventually, as stablecoins.

Their aims remain decidedly altruistic: they intend to revitalize battle-weary communities, reward positive behavior, and encourage community sustainability initiatives. Yet the history of local currencies is littered with broken dreams—as well as critics who question both the utility of blockchain and a localized approach. So what are the chances of success?

What are local currencies?

The idea for local currencies originally centered on a physical note specific to a local area, town or city. In the UK, it took off in cities such as Bristol, Liverpool, Hull, and Exeter; the London boroughs of Brixton and Kingston, plus the geographical area of the Lake District.

The notes can generally only be used in the areas they are specifically designed for, and often come decorated with images of local heroes. For example, musician David Bowie is featured on the front of the Brixton Pound—in recognition of the South London borough where he was born; John Lennon represents Liverpool, and Beatrix Potter, the Lakes.

The idea was that locals exchange these notes in high-street shops, thus supporting local businesses and independent trade.

The Bristol Pound, launched in 2012, was not the first local currency, or the first to be supported by a local council and administered by a credit union. But it was the first to possess all three attributes simultaneously. For this reason, some heralded its success as the start of a new era for local currency-driven localization.

But there was a fair amount of skepticism too, and this year the Bristol Pound’s naysayers were proved right, as the buzz around the project faded, and the use of physical cash diminished in the coronavirus era.

Diana Finch, who runs the Bristol Pound project, told Decrypt that once the credit union which underpinned the project decided to upgrade its system, she and her collaborators finally took the difficult decision not to undertake the necessary and costly upgrade, and instead decided to rethink the whole concept.

The notes officially expire on September 30, 2021, but already they do little more than decorate collectors’ albums. And the fate of the Bristol Pound is not unusual; a study of 82 local currencies developed in the United States since 1991 found that only 17 were still active by 2004.

The Bristol Pound becomes Bristol Pay

But plans are afoot to enact a digital transformation of the Bristol Pound, which aims to relaunch as a blockchain platform and a series of digital tokens by Spring 2022.

It has a new name, Bristol Pay; is built on the environmentally friendly Crown blockchain platform, and will, eventually, become a payment system—pegged to sterling, as the Bristol Pound was. But it will operate at a much more significant scale, according to Finch.

In a radical departure from its prior focus on local businesses, even large supermarkets are now welcome to join. And Bristol Pay will function as a closed-loop payment system for the city, which, according to Finch, will enable it to operate at a fraction of the cost.

Her team estimates that, within ten years, the non-profit platform will operate with funds to spare, and contribute over £3 million a year towards charitable or social enterprise funds.

But, initially at least, Bristol Pay will exist in the form of a token infrastructure to reward positive behavior—“stuff that money doesn’t do,” as Finch puts it.

“We’re looking at how we can play with different sorts of ideas around tokens to measure behavioral flow, or other sorts of uses. For example, how many miles have been cycled, or how many times a coffee cup has been reused,” she said.

The idea is to use interactive measures, such as graphics painted around Bristol, to provide “a citywide metric and engagement tool to get people to think about the impact of their daily choices. We know that people care quite a lot about things like their Uber score, or their eBay score or how many likes they get on Facebook or how many Twitter followers they have, and so I think it’ll as well play on those kinds of motivations that people have,” she explained.

From local to complementary currencies

Meanwhile, the Brixton Pound is planning its own reinvention in digital form. The project has partnered with the Algorand blockchain platform, which is financing the technical build, Guy Davies, a project lead for the Brixton Pound, told Decrypt.

The team envisages a soft launch at the end of the year; they are currently developing the app and building the project’s architecture. But Davies insists that they are not creating another Bitcoin, and that the new Brixton Pound will differ from a local currency because it seeks to complement rather than replace the national currency.

“All local currencies in the UK are pegged one for one with sterling. We are using blockchain capabilities—transparency, security, immutability and accountability—to bolster what the Brixton Pound was doing before via its complementary local currency and grassroots micro-grant giving fund,” said Davies.

It may not be Bitcoin, but the digital Brixton Pound resembles a stablecoin. And the team has partnered with MoneyFold, a UK-regulated stablecoin, for its backbone infrastructure.

But, in keeping with the Brixton Pound’s grassroots approach, they plan to involve the local community in the later stages of the project. “This is the exciting bit; our mantra is ground up, not top down, so getting feedback and input will be absolutely key for its success,” said Davies.

Are local currencies even the answer?

Not everybody is convinced there’s an appetite for local currencies, digital or plain vanilla.

Laith Khalaf, financial analyst at AJ Bell finds the idea hard to reconcile with the modern world: “The whole point of digital currency is to globalise what you do with your money, not contain it to one area,” he told This is Money.

Others consider that digitizing local currencies won’t solve the main issue, which is that local businesses often have nowhere to spend the local currencies they receive, as their suppliers are unlikely to accept them.

In 2019, a study on the effects of the Bristol Pound on localization, by Leeds University academics, found that businesses said the local currency had had no reported impact in encouraging them to deal more with local suppliers; only one out of 27 businesses surveyed saw any effect or impact on local productivity from the scheme.

Yet in other regions of the world, local currencies have seen more success. The world’s longest-running local currency, Switzerland’s WIR, was created in 1934 as war loomed and Swiss unemployment surged. Today, the WIR has more than 50,000 members (17% of the total number of Swiss businesses) and annual revenues of €1.5 billion.

BerkShares, the best-known local currency in the U.S., is another success story; it’s used by more than 400 businesses in the Berkshire region of western Massachusetts.

And Chiemgauer, a local currency used in Germany’s Bavaria region, has been instrumental in community efforts to help companies affected by the coronavirus pandemic. More than 30 companies have made use of the fund it’s set up, and a solar panel initiative, which sees locals paid in Chiemgauer, saw substantial uptake, with significant carbon credits notched up.

But more generally, Christian Gelleri, who founded Chiemgauer, believes unemployment may play a big part in whether local currencies are a failure or a success.

“One successful example in 2019 was the Sardex in Sardinia, with more than 3,000 businesses and a turnover of nearly €50m ($54.7m, £44.4m). The unemployment rate there was 15%. We had €6.3m turnover in Chiemgauer, with an unemployment rate of 1.9%,” he told the BBC.

Local currencies and operating costs

But even if there is a need for local currencies, operating costs have defeated many projects. In the US, the annual $300,000 cost of keeping Philadelphia’s Equal Dollar in circulation eventually led to its closure in 2014, after almost 20 years.

Projects that survive meet this challenge in a variety of ways. The WIR charges a small transaction fee and interest on loans taken out in the currency. While in Canada, the Calgary dollar pays its employees in the local currency and receives funding from the government and local businesses.

But the diminishing use of cash means that local currencies need to function electronically these days. And according to Edward Cartwright, Professor of Economics at De Montfort University, in the UK city of Leicester, local currencies are likely to struggle to meet the significant costs incurred by today’s secure computer systems.

“The local nature of localized currency means there are not sufficient economies of scale to absorb these fixed costs,” he explained.

Blockchain has many advantages, including system security, and platforms that don’t have the environmental problems associated with Bitcoin, said Cartwright. ‘‘But they do not seem a ready solution to the problem yet, because blockchain relies on a large pool of people verifying the blockchain in order to avoid manipulation.”

In his opinion, a localized currency will struggle to have a sufficiently large pool of people to perform verification “in a robust and secure way.”

The heartbreaking tale of Hullcoin

But neither adequate support or environmental concerns were at the root of the problems suffered by one local currency that tried the tokenized approach.

In 2014, the local council for the city of Hull, in the UK’s North East, approved HullCoin, a cryptocurrency coin—based on Bitcoin, which could be earned by citizens for doing good works.

The idea was to use blockchain to embed time-stamped evidence of the positive social outcome activity onto the blockchain.

The project was the idea of David Shepherdson, who was working as anti-poverty officer for Hull council at the time. He and his partner Lisa Bovill founded Kaini Industries, a not-for-profit set up to develop the technology. It received £240,000 in government and charitable funding and originally planned to launch HullCoin in January 2018. But then the project disappeared completely from view.

On a call from Hull, Shepherdson told Decrypt that, by 2018, the project had built out its blockchain platform; it had 80 providers on board ready to accept HullCoin, including social housing cooperatives, prisons and local health services. 120 local businesses and 4,000 students were onboarded for trials.

The kitty was running dry, but HullCoin’s newest backers, one of the UK’s largest charities, the National Lottery, assured the project’s team that within two to three months, £1.4 million in funding was theirs for the taking.

But 14 months later, the funding had still not appeared. The charity restructured its funding policy, and the new digital policy chief proved unsympathetic to HullCoin’s aims.

The charity’s funding about-face coincided with the onset of 2018’s crypto winter, as regulators clamped down and cryptocurrencies fell in value. The loss of funding meant that Shepherdson was destitute; he lost everything, including the team’s prized blockchain developer, Peter Bushell. (Bushell designed the UK’s first home-grown cryptocurrency FeatherCoin, a fork of Litecoin, which is itself a fork of Bitcoin.) HullCoin essentially “fell apart,” said Shepherdson, describing a “bruising experience.”

They tried in vain to get private backing but “[HullCoin] was designed to encourage social inclusion, not from a commercial perspective,” so it wasn’t all that attractive to private investors, said Shepherdson, who now works as a consultant specializing in community systems.

Embracing regulation

Diana Finch is well aware of the regulatory void that many crypto projects currently face in the UK. Bristol Pay is first addressing the technical aspects of the project in partnership with developers Digital Wonderlab, before facing “the difficult bit, which is the regulated financial side, next year or the year after.”

She believes that this should be ample time for regulations around stablecoins and their ilk to become clearer. But, in the meantime, Bristol Pay is being developed on “a shoestring,” with much of the funding coming from “retirement sales” of the Bristol Pound.

Shepherdson, meanwhile, will be watching with interest. While he’s taken a backseat, he still gets emails from people trying to set up a local cryptocurrency. For instance, he’s been approached by a community from Palestine that’s developing an inclusiveness token for the embattled region.

But Shepherdson considers that the likelihood of generating any income from local currencies is low because funding is so grant-dependent. “It might be easier for them now,” he offered. But blockchain and crypto offer no panacea to the problems of establishing local currencies, he believes: “The technology is both a blessing and a curse, because it’s so divisive.”

16 July 2021 14:24